Some books don’t so much tell a story as open a space inside you - a quiet chamber you didn’t know existed until the words arrive. Julian Barnes’s Levels of life is one of those books. I first read it around 2015, and I’ve returned to it many times since, each reading revealing something slightly different.

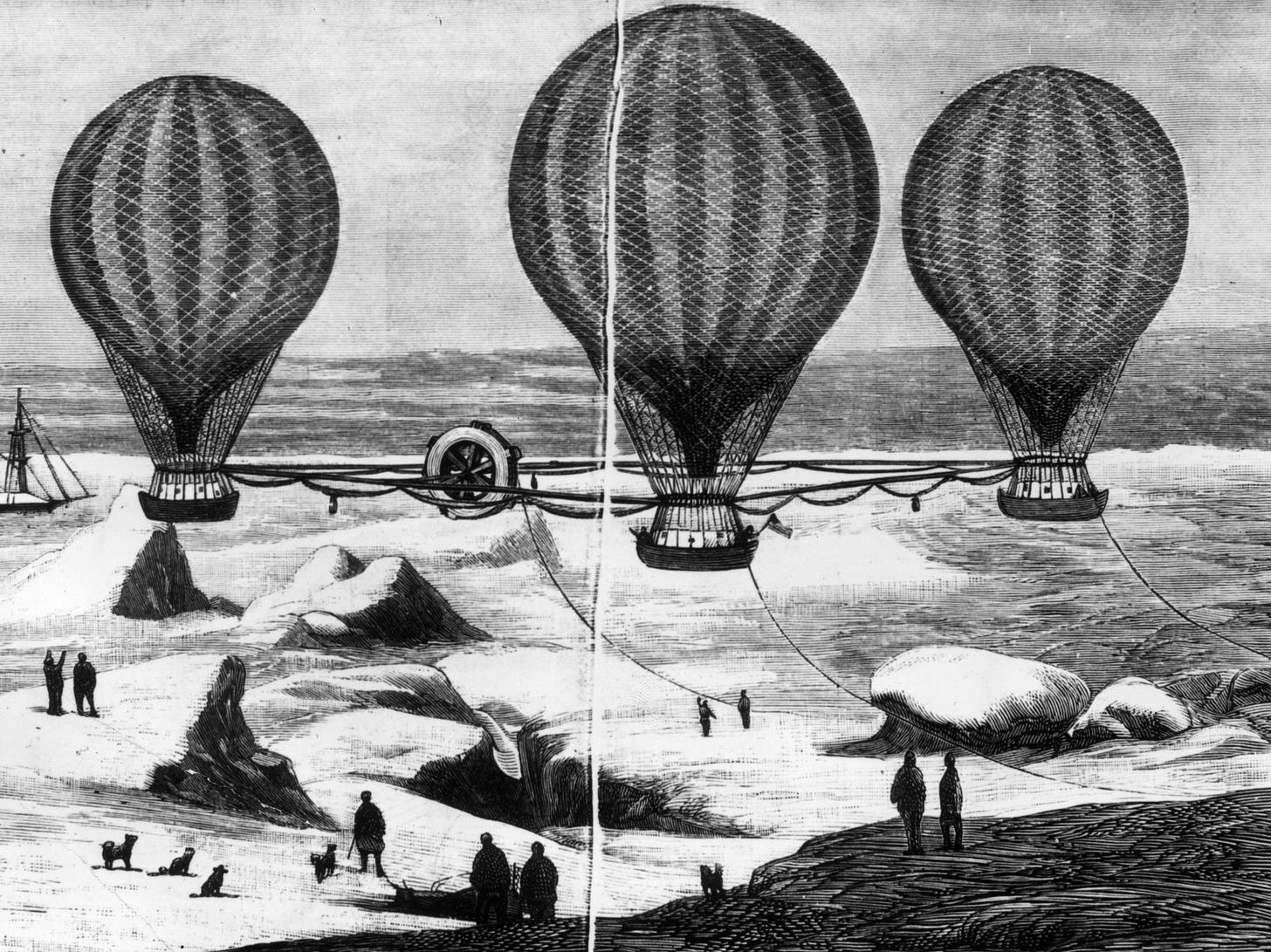

Barnes begins with flight - literal flight, the 19th-century dream of rising above the earth in a balloon. He writes about the human hunger to see from above, to feel that fragile mixture of wonder and danger that comes with altitude. These early pages are whimsical, almost historical, full of floating and invention. But slowly, imperceptibly, he begins to shift altitude: from the lightness of ascent to the weight of descent.

The book’s genius is in that movement. It begins in the air and ends deep underground - in grief, in the unspeakable loneliness of loss. Barnes’s wife, the literary agent Pat Kavanagh, died in 2008 after thirty years together, and Levels of life is his act of mourning. He doesn’t write sentimentally; he writes with surgical restraint. But beneath that precision runs a current of pure ache.

He writes: “You put together two things that have not been put together before. And the world is changed” - it’s a line about love, but also about art. Love, like flight, lifts us - we see farther, feel lighter, believe in elevation. But when love is lost, that same height becomes unbearable. We fall, but we remember the view.

I’ve thought often about that metaphor: how altitude is both ecstasy and risk. Barnes doesn’t offer comfort; he offers clarity. Grief, he says, is a landscape you must learn to live in. “The fact that someone is dead,” he writes, “may mean that they are not alive, but doesn’t mean that they do not exist.” That sentence has followed me for years, especially ever since I lost close relatives - a perfect distillation of what mourning really is: the coexistence of presence and absence, the persistence of the invisible.

Reading Levels of life feels like eavesdropping on a mind thinking its way through pain. Barnes circles his grief patiently, relentlessly, as if repetition might turn bewilderment into meaning. The prose is spare, but the silences between words vibrate. He doesn’t try to resolve loss, only to name it without flinching.

What moves me most is the book’s structure: it begins in the air, with hot-air balloons and impossible dreams, and ends in the body - heavy, grounded, still. It’s as if Barnes is saying that to love is to rise, but to grieve is to stay, to bear the unbearable gravity of having lived.

I often return to Levels of life when I want to remember that literature’s deepest task isn’t to console but to articulate what we can’t otherwise say. Barnes does that with extraordinary grace: he maps the invisible terrain between two people, between life and what comes after love.

Every time I finish it, I feel both wrecked and restored. The book doesn’t lift me, but it steadies me. It teaches that grief is not something to overcome but something to live alongside - a quiet companion, a new level of life.

Thank you for this article I'm trapped in grief . The loss of my wife for over 38 years. And for the loss of me.

Stunnnnnnning reflection! Thank you!!!